Quantifying Architectural Design

02/23/2025, thsu-swk

1.

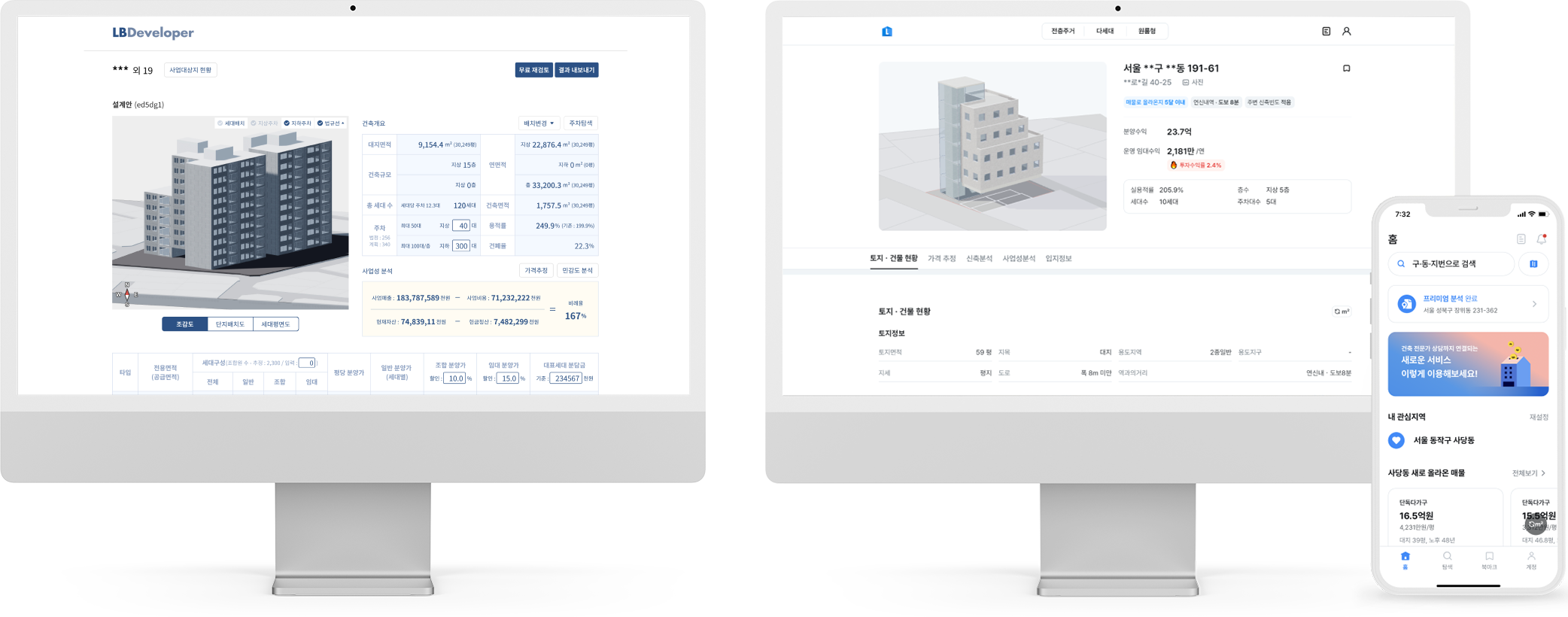

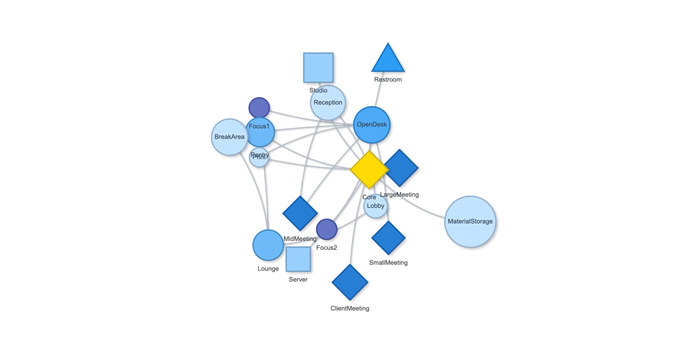

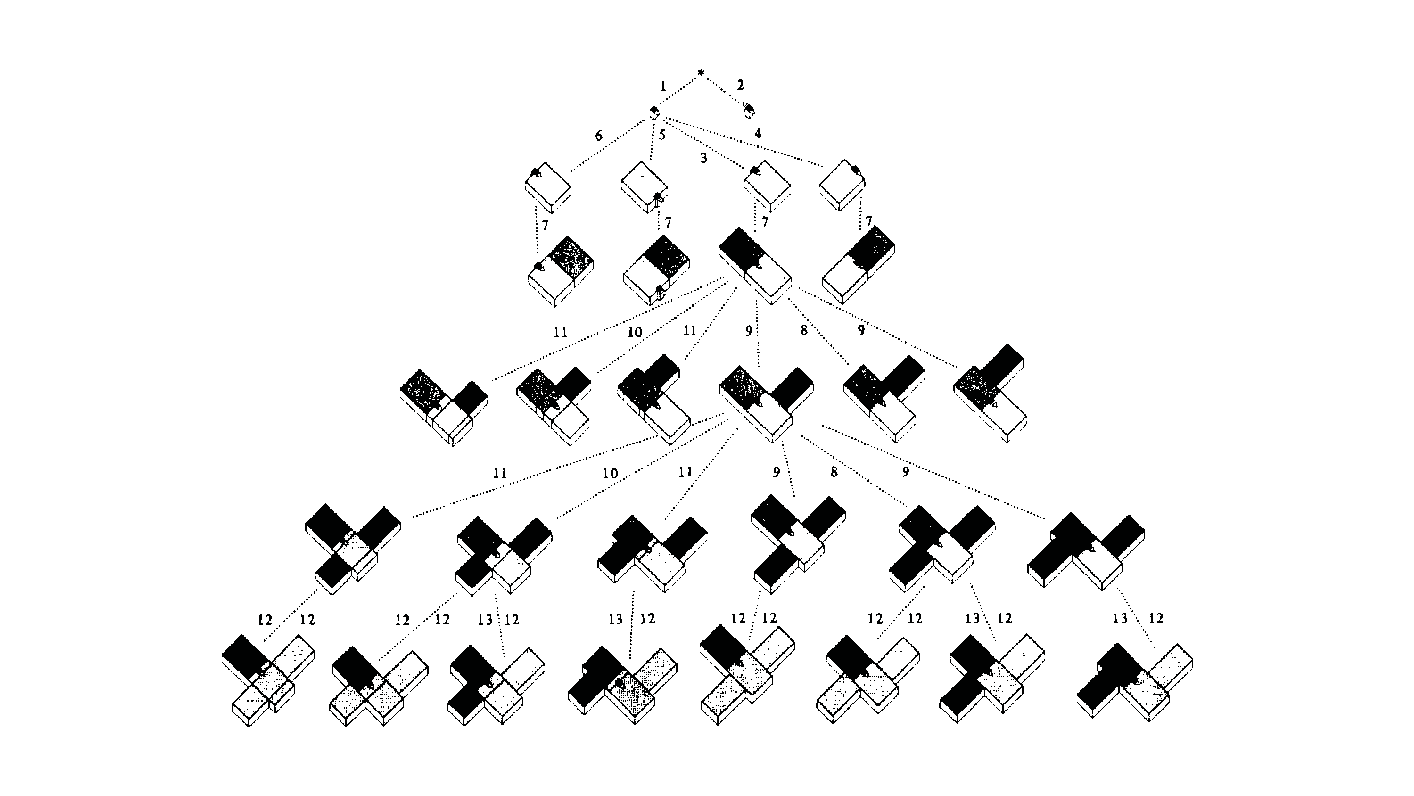

Measurement: Why It Matters In the context of space and architecture, “measuring and calculating” goes beyond merely writing down dimensions on a drawing. For instance, an architect not only measures the thickness of a building’s walls or the height of each floor, but also observes how long people stay in a given space and in which directions they tend to move. In other words, the act of measuring provides crucial clues for comprehensively understanding a design problem. Of course, not everything in design can be fully grasped by numbers alone. However, as James Vincent emphasizes, the very act of measuring makes us look more deeply into details we might otherwise overlook. For example, the claim “the bigger a city gets, the more innovation it generates” gains clarity once supported by quantitative data. Put differently, measurement in design helps move decision-making from intuition alone to a more clearly grounded basis. 2. The History of Measurement Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man Let’s take a look back in time. In ancient Egypt, buildings were constructed based on the length from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. In China, the introduction of the “chi” (Chinese foot) allowed large-scale projects like the Great Wall to proceed with greater precision. Moving on to the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man highlights the fusion of art and mathematics. Meanwhile, Galileo Galilei famously remarked, “Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not,” showing how natural phenomena were increasingly described in exact numerical terms. In the current digital age, we can measure at the nanometer scale, and computers and AI can analyze massive datasets in an instant. If artists of old relied on their finely honed intuition, we can now use 3D printers to produce structures with a margin of error of less than 1 mm. All of this underscores the importance of measurement and calculation in modern urban planning and architecture. 3. The Meaning of Measurement British physicist William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) once stated that if something can be expressed in numbers, it implies a certain level of understanding; otherwise, that understanding is incomplete. In this sense, measurement is both a tool for broadening and deepening our understanding, and also a basis for conferring credibility on the knowledge we gain. Even in architecture, structural safety relies on calculating loads and understanding the physical properties of materials. When aiming for energy efficiency, predicting daylight levels or quantifying noise can guide us to the optimal design solution. In urban studies, as Geoffrey West points out in his book Scale, the link between increasing population and heightened rates of patent filings or innovation is not merely a trend, but a statistically verifiable reality—one that helps guide city design more clearly. However, interpretations can vary drastically depending on what is measured and which metrics one chooses to trust. As demonstrated by the McNamara fallacy, blind belief in the wrong metrics can obscure the very goals we need to achieve. Because architecture and urban design deal with real human lives, they must also consider values not easily reducible to numbers—such as emotional satisfaction or a sense of place. This is why Vaclav Smil cautions that we must understand what the numbers truly represent: we shouldn’t look at numbers alone but also the context behind them. 4. The “Unmeasurable” In design, aesthetic sense is a prime example of what’s difficult to quantify. Beauty, atmosphere, user satisfaction, and social connectedness all have obvious limits to numerical representation. Still, there have been attempts to systematize such aspects—for instance, Birkhoff’s aesthetic measure (M = O/C, where O = order, C = complexity). Some methods also translate survey feedback into ratings or scores. Yet qualitative context and real-world experiences are not easily captured in raw numbers. Informational Aesthetics Measures Design columnist Gillian Tett has warned that over-reliance on numbers can make us miss the bigger context. We need, in other words, to connect “numbers and the human element. ” Architectural theorist K. Michael Hays notes that although the concept of proportion from ancient Pythagorean and Platonic philosophy led to digital and algorithmic design in modern times, we still cannot fully translate architectural experience into numbers. Floor areas or costs might be represented numerically, but explaining why a particular space is laid out in a certain way cannot be boiled down to mere figures. In the end, designers must grapple with both the quantitative and the “not-yet-numerical” aspects to create meaningful spaces. 5. Algorithmic Methods to Measure, Analyze, and Compute Space Lately, there has been a rise in sophisticated approaches that integrate graph theory, simulation, and optimization into architectural and urban design. For example, one might represent a building floor plan as nodes and edges in order to calculate the depth or accessibility between rooms, or use genetic algorithms to automate layouts for hospitals or offices. Researchers also frequently simulate traffic or pedestrian movement at the city scale to seek optimal solutions. By quantifying the performance of a space through algorithms and computation, designers can make more rational and creative choices based on those data points. Spatial Networks Representing building floor plans or urban street networks using nodes and edges allows the evaluation of connectivity between spaces (or intersections). For instance, if you treat doors as edges between rooms, you can apply shortest-path algorithms (like Dijkstra or A*) to assess accessibility among different rooms. Spatial networks Justified Permeability Graph (JPG) To measure the spatial depth of an interior, you can choose a particular space (e. g. , the main entrance) as a root, then lay out a hierarchical justified graph. By checking how many steps it takes to reach each room from that root (i. e. , the room’s depth), one can identify open/central spaces versus isolated spaces. Justified Permeability Graph (JPG) Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA) Divide the space into a fine grid and connect points that are visually intervisible, thus creating a visual connectivity network. Through this, you can predict which spots have the widest fields of view and where people might be most likely to linger. Axial Line Analysis Divide interior or urban spaces into the longest straight lines (axes) along which a person can actually walk, then treat intersections of these axial lines as edges in a graph. Using indices such as Integration or Mean Depth helps you estimate which routes are centrally located and which spaces are more private. Genetic Algorithm (GA) For building layouts or urban land-use planning, multiple requirements (area, adjacency, daylight, etc. ) can be built into a fitness function so that solutions evolve through random mutations and selections, moving closer to an optimal layout over successive generations. Reinforcement Learning (RL) Treat pedestrians or vehicles as agents, and define a reward function for desired objectives (e. g. , fast movement or minimal collisions). The agents then learn the best routes by themselves. This is particularly useful for simulating crowd movement or traffic flow in large buildings or at urban intersections. 6. Using LLM Multimodality for Quantification With the advancement of AI, there is now an effort to have LLMs (Large Language Models) analyze architectural drawings or design images, partly quantifying qualitative aspects. For instance, one can input an architectural design image and compare it to text-based requirements, then assign a “design compatibility” score. There are also pilot programs that compare building plans and automatically determine whether building regulations are met and calculate the window-to-wall ratio. Through such processes, things like circulation distance, daylight area, and facility accessibility can be cataloged, ultimately helping designers decide, “This design seems the most appropriate. ” 7. A Real-World Example: Automating Office Layout Automating Office Layout Automating the design of an office floor plan can be roughly divided into three steps. First, an LLM (Large Language Model) interprets user requirements and translates them into a computer-readable format. Next, a parametric model and optimization algorithms generate dozens or even hundreds of design proposals, which are then evaluated against various metrics (e. g. , accessibility, energy efficiency, or corridor length). Finally, the LLM summarizes and interprets these results in everyday language. In this scenario, an LLM (like GPT-4) that has been trained on a massive text corpus can convert a user’s specification—“We need space for 50 employees, 2 meeting rooms, and ample views from the lobby”—into a script that parametric modeling tools understand or provide guidance on how to modify the code. Zoning diagram for office layout by architect Let’s look at a brief example. In the past, an architect would have to repeatedly sketch bubble diagrams and manually adjust “Which department goes where? Who gets window access first?” But with an LLM, you can directly transform requirements—like “Maximize the lobby view and place departments with frequent collaboration within 5 meters of each other”—into a parametric model. Using basic information such as columns, walls, and window positions, the parametric model employs rectangle decomposition and bin-packing algorithms (among others) to generate various office layouts. Once these layouts are automatically evaluated on metrics such as adjacency, distance between collaborating departments, and the ratio of window usage, the optimization algorithm ranks the solutions with the highest scores. LLM-based office layout generation If humans were to sift through all these data manually—checking average inter-department distances (5 m vs. a target of 3–4 m)—it would get confusing quickly. This is where the LLM comes in again. It can read the optimization results and summarize them in easy-to-understand statements such as: “This design meets the 25% collaboration space requirement, but its increased window use may lead to higher-than-expected energy consumption. ” Some example summaries might include: “The average distance between collaborating departments is 5 meters, which is slightly more than your stated target of 3–4 meters. ” “Energy consumption is estimated to be about 10% lower than the standard for an office of this size. ” If new information comes in, the LLM can use RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) to review documents and instruct the parametric model to include additional constraints—like “We need an emergency stairwell” or “We must enhance soundproofing. ” Through continuous interaction between human and AI, designers can explore a wide range of alternatives in a short time and leverage “data-informed intuition” to make final decisions. results of office layout generation Essentially, measurement is a tool for deciding “how to look at space. ” Although determining who occupies which portions of an office with what priorities can be complex, combining LLMs, parametric modeling, and optimization algorithms makes this complexity more manageable. In the end, the designer or decision-maker does not lose freedom; rather, they gain the ability to focus on the broader creative and emotional aspects of a project, freed from labor-intensive repetition. That is the promise of an office layout recommendation system powered by “measurement and calculation. ” 8. Conclusion Ultimately, measurement is a powerful tool for “revealing what was previously unseen. ” Having precise numbers clarifies problems, allowing us to find solutions more objectively than when relying on intuition alone. In the age of artificial intelligence, LLMs and algorithms extend this process of measurement and calculation, making it possible to quantify at least part of what was once considered impossible to measure. As seen in the automated office layout example, even abstract requirements become quantifiable parameters thanks to LLMs, and parametric models plus optimization algorithms generate and evaluate numerous design options, proposing results that are both rational and creative. . .